This is Part Two in our series, 'The Future of ID is Mobile'. Missed Part One? View here.

The strategic question to be asked is, “Why are Caribbean countries continuing to focus on implementing classic physical ID cards (albeit eID cards do carry more information securely)?

There is no reason why the Caribbean countries should, yet again, lag behind the rest of the world. There is no excuse on budget terms, as focusing on implementing mID apps will be less expensive than producing physical ID cards – more on this aspect later in this article. Suffice to say that according to the World Bank, “the prevalence of mobile phones and the relatively low cost of some mobile IDs compared to a card-based system can make this an attractive option.”

To make the move to mIDs viable requires a very significant penetration in the mobile device and mobile internet market. So how does the Caribbean stack up to this comment on the capacity for mobile phones and mobile internet capacity?

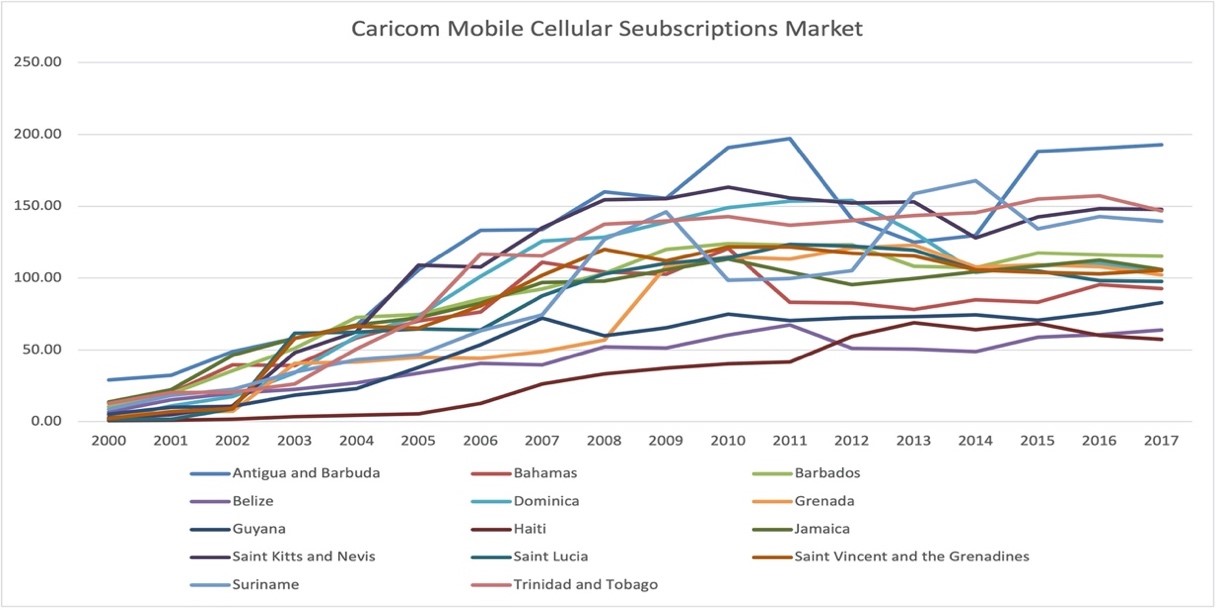

According to the World Bank, many CARICOM countries have in excess of 100% market penetration for mobile subscriptions. Those that do not have more than 60% market penetration.

Figure 1 Mobile Subscription rates % : Source Extract from International Telecommunications Union (ITU) statistics

Figure 1 Mobile Subscription rates % : Source Extract from International Telecommunications Union (ITU) statistics

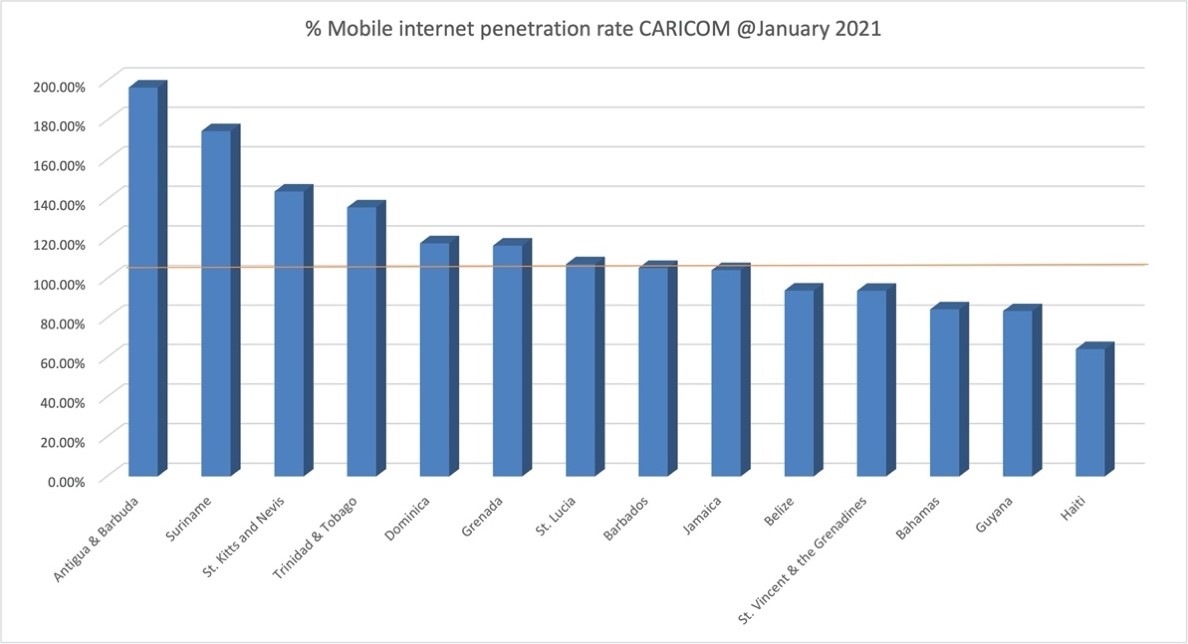

Figure 2 Mobile Internet Market Penetration % : Source - data extract from Stastica

Figure 2 Mobile Internet Market Penetration % : Source - data extract from Stastica

The question may be asked, “What is the likelihood of citizens using a mobile device-based digital identity system? Clearly, the population demographics combined with the availability and accessibility to both mobile devices and the internet would seem to provide a solid foundation to determine the potential success of migrating to an mID environment.

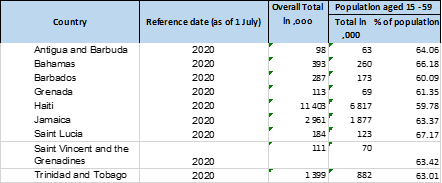

According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, the demographics of the CARICOM countries, for which information is available, show that at least 60% of country populations fall in the age category of 15 – 59 years. This seems to be a reasonable and conservative metric to take account of the fact that:

- some countries do not require national identities for children under the age of 12;

- not all children below the age of 15 would necessarily have access to mobile devices, and

- those 60 years and older may not have the competence or confidence to use mobile apps of this nature.

This basically means that taking the 3 metrics of population demographics, internet penetration, and mobile subscriptions there is a very good case to be made for a number of Caribbean countries to move to mobile national digital ID systems rather that the potentially expensive and soon-to-be redundant physical eID cards.

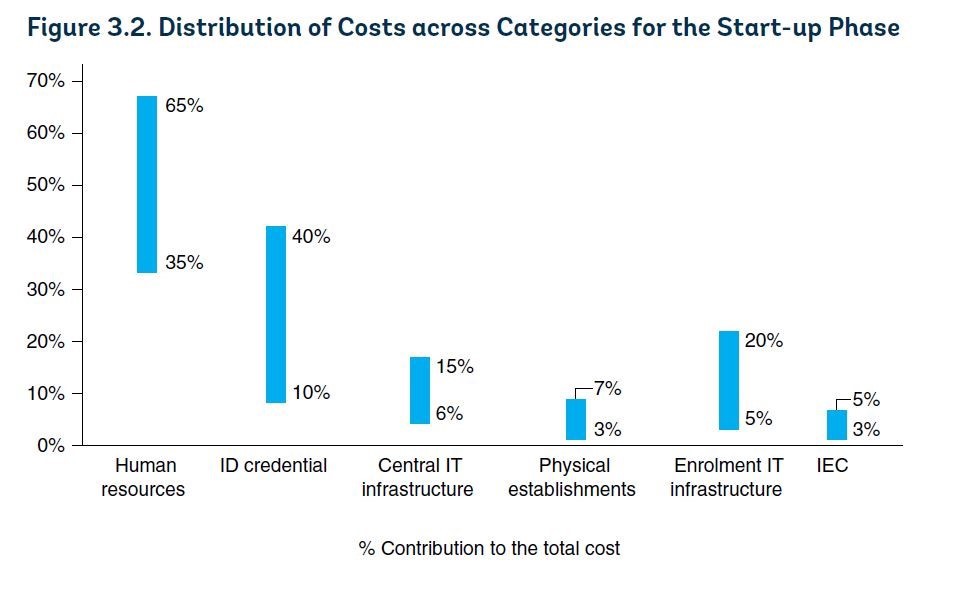

As mentioned earlier in this article, the cost difference of implementing an eID card-based system, compared with an mID system, can be very significant. The World Bank Group has produced a detailed analysis of the cost categories for implementing digital ID systems. As can be seen from the percentage of the total cost of a national digital ID implementation associated with just the issuing of eID cards ranges between 10% and 40%. The wide range relates to the type of card issued and its functionality.

The study states that “a design choice with significant cost impact is the use of chip-based smart cards as an ID credential. When compared to other types of ID credentials, chip-based smart cards incur higher costs for design, printing, and distribution.”

Given that the national ID projects in the Caribbean are primarily focused on implementing ID cards with microchips embedded like eID cards, the cost impact would be at the higher end of the scale, in the 40% range. However, based on the assumption, previously mentioned in this paper, regarding the population demographics that could use mID and those that might require an eID card, the savings of focusing implementation of a mobile ID solution with eID card issuing as the “back-up” solution rather than the primary solution could save governments between 20 – 25% of the total cost of the project.

In addition, focusing on implementing mID solutions is future-proofing the national identity system.

Unfortunately, this appears to have been a missed opportunity for those Caribbean countries already engaged in implementing digital identity systems. Caribbean countries could have become world leaders and visionaries in the Mobile Digital ID domain by shifting the focus away from the implementation of physical eID cards.

Caribbean governments, particularly those who may be considering, but have not yet implemented digital ID systems, need to be bold and grasp opportunities to implement cutting-edge systems based on emerging technologies and trends, rather than implementing what is current. Technology moves quickly, “the current” is already cloaked in obsolescence.