The global lockdowns brought on by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 brought with it a demand for video conferencing, virtual classrooms, and the use of collaboration tools to facilitate the work environment. At the height of the pandemic, Zoom added 2.22 million additional users in 2020 which was more than the entire 2019 while educational tools like Google Classroom saw their user base double to over 100 million.

The Caribbean region was not exempt from these realities. In fact, the public sector across the region saw a significant upsurge in the use of such services, particularly as remote work environments and virtual classrooms became necessary. The pressure to find solutions to facilitate business continuity led to short-term decision-making based on expediency. With those goals met through the use of online tools like Go-To-Meeting, Cisco, Microsoft, Zoom, and Google, the region was forced to create a plan of action for the medium and long term.

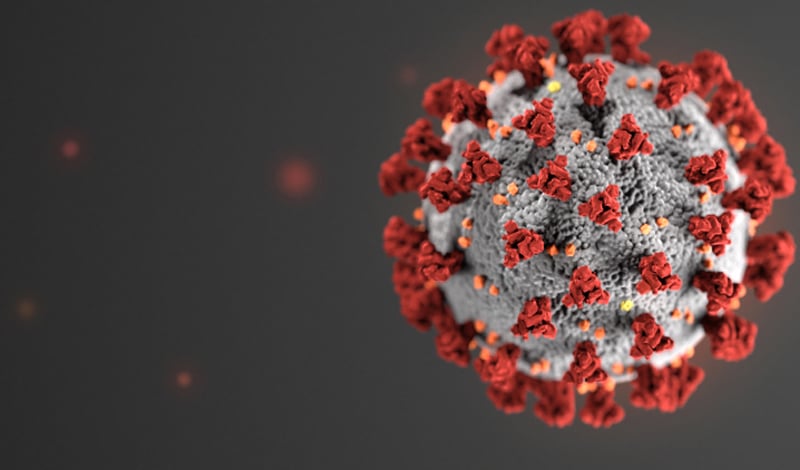

A close examination of the science surrounding the COVID-19 virus has made it clear that this, and future pandemics are likely to be more than just one-off occurrences. That said, organizations in both the public and private sectors have been on the hunt for strategies that ensure a more nimble reaction to socially disruptive events. Now more than ever, opportunities exist for Caribbean governments to adopt holistic approaches to such social disruptive events which not only covers national health-impacting epidemics such as COVID-19, SARS, Ebola, etc. but also natural and man-made disasters.

Resilience Through Self-Reliance

At the core of any strategic approaches by Caribbean governments should be the concept of “self-reliance”. This core objective should be at the heart of any national and/or regional strategic initiatives to mitigate risk in the domain of ICT.

One of the primary collateral outcomes emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic has been the perceived “need” by individual governments to control the manufacture, distribution, and export of personal protection equipment (PPE). Demonstrated by EU laws concerning PPE & export laws, and US laws that were similar. Could this need to control resources, including ICT, spread to other areas of the economic and social activity that now may be considered strategically critical at a nation-state level?

For the medium-term, it appears that many governments will require those who can work from home to continue to do so. The tools (such as video conferencing and collaboration platforms) that allow a remote working approach to be sustained thus become critical strategic national infrastructure. Similarly, the use of virtual classroom platforms may also become a strategic resource. The rapid upsurge in the use of the Google Classroom platform and clearly the strain on the existing infrastructure has prompted Google to issue guidelines on its use to ensure the quality of service. Given that almost 50% of students in the USA use Google services could the government of the USA require that priority be given to USA-based students?

How would that impact other countries, particularly regions such as the Caribbean, where none of the main players in remote working/collaboration have localised infrastructure?

What can be clearly stated is that, in the current COVID-19 climate, Caribbean governments have outsourced critical national ICT services beyond Caribbean jurisdictional reach.

It is critical that, rather than accepting this precarious status quo, Caribbean governments must urgently refine their strategies to ensure long-term control and sustainability. There are three key critical aspects to a holistic strategic approach to ICT deployment that Caribbean governments must contend with:

- Access

- Data sovereignty

- Data privacy

- Platform Security

.jpg?width=800&name=CC%20Blog%20Banner(1).jpg)

Platform Access

This relates to the capacity of a nation-state to ensure uninterrupted access to critical ICT platforms. Can a government ensure that it has both physical and jurisdictional control to access a particular environment?

Platforms such as Zoom, Microsoft 365/Teams, and Google Services operate in their respective public cloud environments. Caribbean usage of these environments requires access predominately to US-based data centres for both applications and storage.

This approach eliminates any possible control, by Caribbean governments, to ensure access to these services.

Data Sovereignty

As indicated above in “Platform Access” the principal service providers have no infrastructure located in the Caribbean, this presents a significant data sovereignty issue for Caribbean governments. Where data resides, particularly sensitive or personal data can be critically important. For example, data that resides in the USA is subject to the Cloud Act.

Concerns by the European Union over mass surveillance by US authorities of EU citizen data stored on USA located servers led to the implementation of the EU-US Privacy Shield agreement. This requires American companies providing US-located cloud storage to be certified for compliance with the EU GDPR.

Currently, the Caribbean has no such legislation to protect access to personal data. The surge in the use of cloud services for video conferencing, work collaboration, and virtual classrooms further expose potentially sensitive data of Caribbean citizens to ex-jurisdictional access and use.

To learn more stay tuned for Part 2, where we discuss the other critical aspects of a holistic strategic approach to ICT deployment.